Freedom of the press is fundamental to a functioning Democracy.

One of the pillars of a free press is the public’s Right to Know.

Both were threatened last week after Attorney General Tim Fox made a public display of denying an open records request by Associated Press reporter Matt Gouras.

In the days following Fox’s announcement that he would not fulfill the AP’s request for information on concealed carry permit holders in Montana, Gouras and other Montana AP reporters began receiving threats online.

Here are just of the few of the most sinister threats:

In another online forum anonymous commenters posted Gouras’ home address and even a Google Street View photo of Gouras’ house.

The Associated Press declined to comment on the threats.

Fox’s spokesman, John Barnes, said in a statement that the Attorney General’s Office was not aware of any threats made against AP reporters or their families.

“If employees of the Associated Press – or any citizens – have received threats, they should contact their city police department or county sheriff office,” Barnes said via email. “The Montana Department of Justice can assist in investigations when requested by local authorities.”

This all stemmed from Gouras’ March 18 request for public information on current concealed carry permit holders, including, but not limited to, last name, first name, middle name, street address, city, employer, age or date of birth, driver’s license number, date of application.

Earlier this year the Montana Legislature passed a law, which Gov. Steve Bullock signed, barring the state from reveal information on concealed weapons permit holders to the press or the public. The law is set to take effect on Oct. 1. The AP made the request before the law had even passed before it was signed into law.

In a July 17 memo Fox denied Gouras’ request for the information citing the Montana Constitution’s privacy provisions. Rather than send Gouras notice denying the request and move on as is customary, Fox chose to grandstand and go on a media blitz, talking about his decision on NRANews.com’s Cam & Co. radio show, as well as making appearances on local television and radio news stations across the state.

(Update 8/5/2013 5:10 p.m.) According to Fox spokesman John Barnes, the Attorney General’s Office sent the July 17 memo only to Associated Press reporters Matt Gouras and Matt Volz as well as to county attorneys and Montana sheriffs. Barnes said he doesn’t know how other media outlets found out about the memo but that there was no effort on the attorney general’s behalf to publicize the decision. Barnes said after the news got out other media outlets requested Gouras’ original request.

Fox called the AP’s request “pretty unprecedented,” a “bad idea” and said:

“Quite frankly I can’t think of a reason where it would be legitimate or reasonable to publish this amount of information or to release it to any individual.”

To the average person not regularly involved in news gathering and public information requests, Gouras’ request might seem intrusive. In actuality, the press requests this kind of information all the time. Good reporters regularly request all kinds of documents, information and data from Government agencies. We usually ask for as much detail as we can get and then work back from there. Sometimes privacy laws dictate what information we can and can’t have, in which case we work out those details with the agency. We make a habit of doing this on the public’s behalf. It’s how we find patterns in mounds of data. It’s how we hold government accountable.

The Associated Press has a long history of this kind of reporting. It was not too long ago Gouras uncovered the fact that hundreds of people barred from having guns because they are felons on parole or probation were still able to get hunting licenses in Montana with no questions asked.

Gouras didn’t publish the names of everyone who had a hunting license. He didn’t reveal a list of all the felons and parolees in the state. He cross referenced two sets of data and developed a good story from what he found.

The reaction from the pro-gun world was swift and harsh as the headlines on conservative blogs and traditional media outlets alike questioned not Fox’s denial of a public records request, but the AP’s motivations in making it in the first place.

The message from the online pro-gun forums was clear: the public doesn’t have a right to know who holds a concealed carry permit. Some extremists made that point even sharper by warning other journalists that making such an request could be a mortal sin.

Such threats and intimidation tactics toward journalists should not be tolerated anywhere, particularly in a country whose founding document enshrined freedom of the press in the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

The biggest critique against the AP’s request for the information seems to be the fact that they wouldn’t comment on what they intended to do with it.

The beautiful thing about the public’s Right to Know is that it’s our Right to Know. We don’t have to tell the government why we want the information or what we plan to do with it. It’s the government’s job to turn it over and it’s the journalist’s job to deal with the data and information in a responsible manner.

People will point to the incident last December when a New York paper published the names and addresses of local gun owners.

You could argue that was a poor decision on their part. I think most journalists would argue right alongside you.

But one newspaper’s poor decision does not mean every journalist who requests information will disseminate it in such an irresponsible manner.

In Montana there is a history of great news reporting stemming from similar requests.

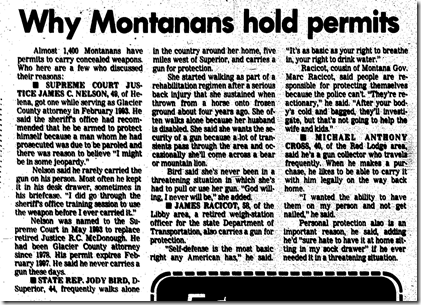

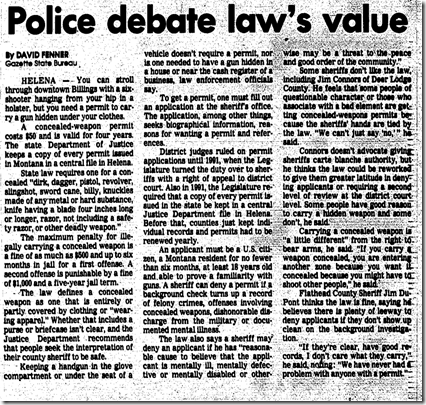

In 2008 then-Lee Newspapers state bureau reporter Jennifer McKee wrote a story on how nine sitting lawmakers had permits to carry concealed weapons.

In 2000 the Missoulian published a story on how the number of concealed weapons permits was climbing.

In 1994 Lee Newspapers capitol bureau reporter David Fenner did a series of stories on concealed weapons in the state. The top story in the January 23, 1994 edition of the Billings Gazette featured a four-part report on gun-bearing Montanans, including an analysis of the concealed carry permit database.

One of Fenner’s stories explored the rise in permit holders.

Another featured interviews with concealed weapons permit holders, including Montana Supreme Court Justice James Nelson, former State Rep. Jody Bird, D-Superior and former Gov. Marc Racicot’s cousin. Presumably

A third story explored how a small community near the Hi-Line saw a spike in concealed weapons permit applications after a security manager at a local mine warned of the dangers of “environmental extremists.”

A fourth article debated the concealed weapons law’s effectiveness in deterring violent crime:

Update (8/5/2013 3:50 p.m.): Just last Thursday in the Outdoors section, the Tribune did a story on women carrying concealed weapons that would not have been possible without substantiating the information with the government. It gave insight into an important story in a responsible way.

So yes, there are “legitimate” and “reasonable” reasons for requesting this kind of information.

Associated Press Bureau Chief Jim Clarke gave me this statement about Gouras’ request and the AP’s intentions for the data Fox refused to turn over:

“After the Montana Legislature voted to remove from the public record information on whom the government had granted permits to carry concealed weapons, effective Oct. 1, The Associated Press requested a database of these files that had long been accessible to the public.

AP acted under freedom of information law, which we do routinely in seeking records at the federal, state and local level as part of our newsgathering process and our long-standing mission to assure transparency and accountability in government. Montana’s Constitution contains such a Right to Know clause, which says: “No person shall be deprived of the right to examine documents.”

We have never had any interest in publishing the Montana database in its entirety.”

It is unclear at this point if the Associated Press or other news outlets plan to sue in court for access to the records.